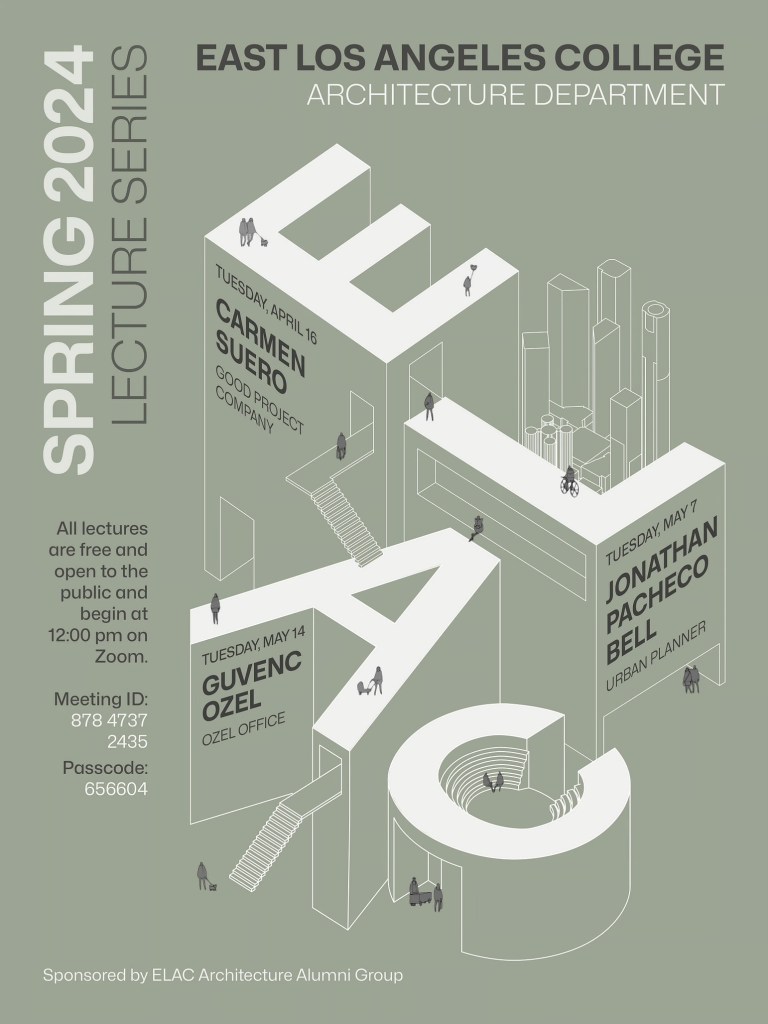

We’re building the future of architecture.

I’m on the Host Committee planning the February 7th annual fundraiser for the nonprofit Architecture + Advocacy. This year’s topic is: “Deconstructing “Engagement: A Conversation about Community-Led Design.”

Community leaders, architects, policymakers, developers, and all people who care about the future of our city, will explore ways community engagement can go beyond “checking a box” and empower residents as decision makers. You can look forward to:

- Meeting other people who care about ending neighborhood inequality

- Participating in an intergenerational discussion about community-led design

- Eating delicious food from local chef, The Aisha Life

- Bidding on (and maybe winning) a wine tasting, task chair, and more!

- Listening to good tunes

Date: Saturday, Feb 7, 2026

Time: 5:00 – 8:00pm

Location: Western Office Showroom, 515 S. Figueroa Street, Suite 101 Los Angeles, CA 90071

Early Bird Tickets: $40

Early Bird ticket sales end January 22nd! After that, the price increases to $50. Get yours now! Tickets: https://architectureandadvocacy.org/en/events/p/architecture-advocacys-annual-fundraiser

Infographics designed by Julia Chen

You must be logged in to post a comment.